Jerome Stueart

(TW: this essay contains frank discussions about sex, sexuality, body image, religion and being queer.)

(a previous version of this essay originally appeared in Fat & Queer: An Anthology of Queer and Trans Bodies and Lives, ed. Morales, Grimm, Ferentini. Jessica Kingsley Publishers, 2021.)

I had a little art studio for one year. A place for all my paints, my canvases, my artistic dreams. A place to be alone, to create masterpieces, to rock out to music, to be myself, to grow and learn.

Then, a year later, the art studio was completely erased, as if it had never been there.

All the walls were taken down; the room became a much larger gallery. You couldn’t find it if you didn’t know where it had been. If you didn’t know my window, you couldn’t see any fingerprint of where I had been.

While the studio was there, that brief year, it changed my life. It gave me a better understanding of my body — something I had never really seen before. It gave me back my sexuality — something taken from me by evangelical churches. It let me see myself as a work of Art — something I never would have believed.

While I struggled to create art, the studio worked on creating me.

For decades, Front Street Studios in Dayton, OH, had used an old Singer Sewing Machine factory as living space for artists. A set of imposing red brick buildings, some two story, some three, with giant fifteen foot windows, sat next to a very active set of railroad tracks, with a river not far away. Over a few decades, the old factory had gone to seed, become unlivable, a place for drug deals and fire hazards. A few years before I got there, it was taken over by new management. The new owners cleaned it up, bought out whoever was still there, and turned it into studio spaces for artists, with open studios twice a month where people from Dayton could come through, wine in hand, and visit your studio and buy your Art. The new owners brought in live bands outside, sold burgers and hot dogs on those open studio days. You’d never have known the place was abandoned and trashed just a few years before.

In the Summer of 2018, needing more studios to rent, the owners divided a larger studio space into smaller 300 square foot slots with giant warehouse windows. They aimed these studios towards artists who didn’t need a lot of space, and didn’t have a lot of money.

Perfect for someone like me.

That summer, I had decided to turn my hobby of portrait painting into a small business, and I needed a small space. I was an adjunct English teacher at a local university, but that didn’t really pay the bills. I struggled a lot. I knew that each semester I would have to beg the chair of the department for any classes he could give me.

So, I needed another source of income.

I had a passion for Art. I had created art before, as a teen, in my twenties. My portrait business had been revived a few times when I needed it. Why not turn it into something more? Why not give it a bigger chance? The owners interviewed me, liked me, and gave me the space for a mere $250 a month. I was in! I had my own space.*

It was the perfect size for me. High ceiling, tall unfinished white drywall, those giant windows that let in the sun — full blazing in the summer! And privacy. I could do anything I wanted in that room. I didn’t have to share this “office space” or justify what I was doing to anyone. It wasn’t part of a job. I had complete control of me in this space. I loved that freedom. I still love it, in my memory, even though the studio is gone.

I had never owned a studio before, a place outside the apartment I lived in, but, to me, having a studio meant that I was “taking my art seriously.” I was taking myself seriously. So I was there every day that summer, working on painting, even as the studio worked on me.

Queer people have to learn early to own themselves and their bodies because we’re told that the spaces are not for us in this world, and sometimes, our own bodies are not for us. Society likes to tell people what they can and cannot do with their bodies, their behavior, their minds. They rent space in our heads, sometimes the whole factory in our head. And in those studios are how we should dress, how we should act, who we should be.

I was raised a Southern Baptist Christian boy–Baptists didn’t dance, didn’t cuss, didn’t drink, and, in my opinion, Southern Baptists are frightened of their bodies. In this fog of unreason, it took me until I was 34 to realize I was gay. I had no space in my head for what it meant to be gay. I was a kid during the AIDS crisis, and that was the first time I had heard about queer people. When you grew up in the Midwest or West Texas, in the rural areas, the Queer Trains didn’t get that far — and the books, movies, people who are strongest in their identities — who might show you who you can be– couldn’t reach you. At least they couldn’t in the eighties. So I didn’t know myself.

I knew to be afraid of my body — and the temptations of Lust we heard about at church. I knew my body was supposed to be attracted to women, and attractive to women, and as a good Christian boy, I should be looking at marriage in my early twenties, if not before. Needless to say, I read a lot of Christian marriage books, people! I also knew that men around me did not talk about their bodies. The boys talked about their desires for women, but that’s not the same thing. Once they were married, it was as if they had joined a secret cult where they were no longer allowed to discuss their bodies, their sexuality, their desires anymore. “You’ll learn about that when you get a girlfriend.”

I knew to be careful not to show I had any sexual feelings because all sexual feelings were bad. Even the straight ones! I mean, you were supposed to have them, but never talk about them or show them. And don’t touch yourself, young man. So masturbation was off the table. It wasn’t even talked about. No one said the word. You had to have a private conversation like you were in a confessional–and talk about it seriously–to even bring up the subject. You weren’t going to talk about it like it was fun, no. It was such a taboo subject I was convinced that no one else felt any urge to touch themselves. I knew a young man who got married because he needed sex and he wasn’t allowed to touch himself or God would be angry with him. So he married a woman as a sanctioned way to release.

“Get married so you don’t sin” was the simple way of staying in God’s favor, and I imagine it has fueled a lot of young, young marriages.

Queer people are watched, all through our lives. Before we discovered I was queer, I was watched by my parents, by my friends, teachers, pastors, as they looked for signs that I was on the Path of Straight Salvation. I should struggle openly with wanting sex with women. I didn’t give them the right signals, though, and we concluded I was broken. The stuff just doesn’t work on me. Which sometimes was its own ironic blessing. At my alma mater, a Baptist university, I got a reputation as a man who had “mastered his body”! I had overcome temptation! (They thought I was immune!). Truth was, my sexuality was buried so deep — it was made invisible. It was erased.

I had to draw it out again.

I had to give it some time to grow and breathe.

But I had to discover it first. That would be when I was 34. That’s a whole story on its own, with many reasons why it took me so long to figure it out. When I discovered I was gay in 2004, it was such beautiful relief to know I wasn’t broken. But I also didn’t know the directions to my own body or mind, nor did I have people around me to mentor me at the time. I had a lot to learn about myself, and a lot to unlearn about my body, about my perception of myself, about what was attractive. It took me a long time to figure out who I was and what I wanted — and even by 2018, 14 years later, there was still work left to do inside my head.

I didn’t know what I didn’t know.

Queer people need a “space” to figure out who they are when they are surrounded by a world of people so unlike them. They need time to figure out what they like, what they feel like doing, what aspects of gender conformity to keep, what to toss. Even queer people in the age of queer visibility still need to find their path in a highway system of How to Be Gay and How to Be Lesbian and That’s All There Is messages given to us today. We are lucky that so many new voices are speaking out about their very different paths to find self-fulfillment, painting their own stories so vividly.

At first, in my new studio, I didn’t know what I wanted to paint, and I didn’t want to waste time. I tried writing in there. I set up a little office. I attempted to tap out some stories. Instead, I just tapped out. It was so hot. It was about 85 degrees inside the studio. I had afternoon light, and a glorious sunset over Dayton in the evening, but no curtains. That afternoon sunlight turned the studio into an oven.

I bought a fan. I bought two fans. I bought three fans.

Eventually, I tried to regulate hours so that I didn’t land there between 1–6pm, but that was a good chunk of the part of the day that I liked. I preferred coming late morning and staying till 10 or 11pm. So, instead of escaping the afternoon heat, I opened windows, used the fans, and dressed accordingly.

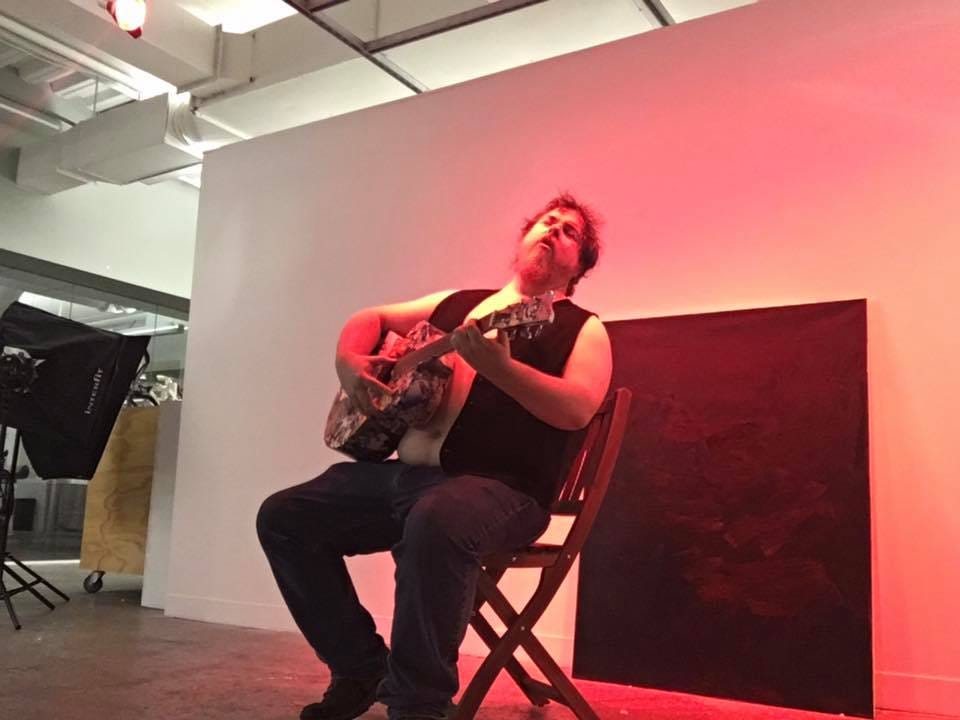

I started wearing a sleeveless shirt with snaps that I could open when I was alone. I had a belly, and I was always raised to believe that men did not walk around a workplace showing their body. After all, there were other artists in the building working. No one else was around in my studio though, and so I wore the shirt like a vest, or went shirtless. I thought it was indulgent and kinda sexy. And completely taboo! I was nervous of anyone seeing my body. I just thought it was wrong, especially if you looked like me.

Remember, I had never liked my body. I grew up skinny, in my mind way too thin, and then I started gaining weight when I was thirty, and I kept going, and now I no longer had an accurate idea of what I looked like.

I had never seen what I looked like, lately. Never as a full-bodied man, outside of a Kohl’s mirror in the dressing room, and had a very unrealistic view of myself. We all have the bathroom mirror impression (light in your face, mirror stops mid chest) and the “I can look down at myself” view — which narrows the view as you look farther down. And the arm-stretched-as-far-as-I-can-go selfie. I knew I wasn’t the accepted media-influenced, societal definition of “good looking”. I knew I was not “well-built” — soft around the edges. I had some body dysmorphia going on. But I was getting curious to know what I looked like. I started taking pictures of myself in the studio to see what other people saw when they saw me.

I didn’t know how big I was. I grew up a skinny kid for 30 years, always underweight for my height. I kept that image in my head for a long time until I noticed myself in other people’s photos and thought–who is that? It would always surprise me how large I was compared to other people, especially other men. I always thought I was the smaller, “weaker” one when I compared myself to other men.

So I set up my ipad to take pictures of myself from a distance. I wanted to see my whole body from the side, from angles you can’t catch in a mirror. I wanted to know what people saw when they saw me.

In my own private space, with my own iPad, I could take pictures of myself shirtless. I could take pictures of myself in my underwear! Hello, Jesus, I could take pictures of myself naked.

Guys I had chatted with online had wanted naked pictures before, and I never felt good about sending a picture of my body online. There are many good reasons not to send nudes through the internet. However, there are NO good reasons not to take one. You can learn a lot about yourself. About the way your body looks. And not just standing up, but relaxing against a window, or lying down, or with special sunlight on your body. I needed to see what I looked like naked. I know, it is hard to believe that I hadn’t really seen myself naked, but I hadn’t from a distance or in a full length mirror.

So I started taking pictures of myself.

We all have our bodies we are attracted to. I was into “bears.” Big, hairy men with soft curves and big arms and kind faces. I was attracted to large men, fat men, big men, huggable men.

When I saw these new pictures of myself, the first thought I had was: I am one of those men.

However, I was not the size I thought I was. I was larger. I was much wider from back to front than I had ever seen. I was thick. My pecs were soft wide pillows that stretched under my arms. My belly overlapped my belt. I had some really nice curves, and an undefined ass.

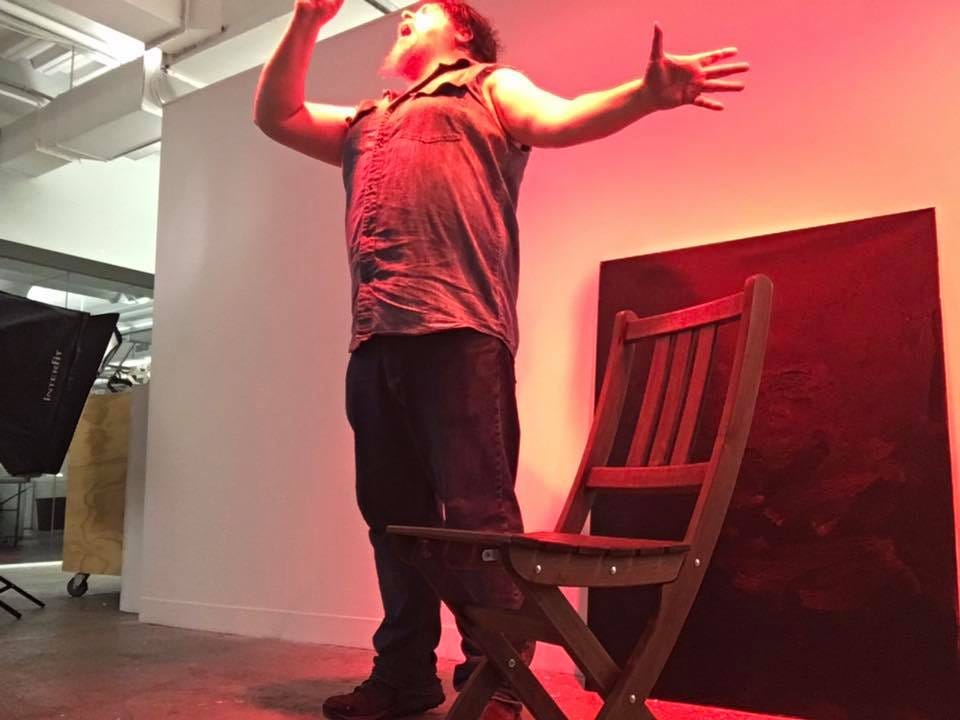

But my initial surprise gave way to love. I loved this body. I was not who I expected I was, but I was okay with that. I began to sympathize and empathize with the man in the pictures. I started acting more comfortable in my body for different pictures, different poses.

You’d think I’d be painting!

Instead, I was creating with my body and my iPad these pictures of a heroic fat queer man, dancing, being sexy, being goofy. Just to see what that looked like. I changed filters and created some of the best pictures of my beautiful fat body. What about this Noir setting? Or this Dramatic Cool? Or Vivid Warm filters? I used the different adjustments to work the saturation levels, the definition, the exposure, and had fun using my body as the subject of my own artistic exploration.

I even chanced answering requests for pictures from long-time gay friends, gaining consent, and sending these nudes to men I was talking to. I was suddenly not afraid if the nudes got out into the world. These were artistically done, and completely sent with consent. I had nothing to fear from my body. My body was teaching me who I was.

I wasn’t perfect, but I wasn’t as unattractive as I thought I was. And even if I was, I could work that body. And I noticed in the pictures how much more attractive I became when I became fearless in my mind. When I let loose. When I stood tall.

I was everything visually I admired in other men.

Then I started wondering something even deeper, and more taboo. What did I look like having sex? I’ll be honest. I had not had a lot of sex. Old beliefs. Fears of pain. Embarrassment over having so little experience. So, I never wanted to see myself or think of what I looked like during those moments. But while I had this studio, this private place, and this way to dissociate from my body by watching it through a screen and seeing it as both other and self, I needed to explore places of vulnerability and ecstasy.

Why was that important?

Sexuality and queer sexuality especially is taboo to talk about in religious circles where I had grown up. I did not have the safety of a space — a “studio” — to talk to others about sexuality, about their bodies. I never talked about myself sexually with other people. I wanted them to pretend I never had sex. That was okay. I didn’t want them to know. I pretended they didn’t have sex either! I really didn’t want my straight friends and allies to know I had ever had a sexual thought. I didn’t take my shirt off when we played basketball in high school. It took me a long time to feel comfortable undressing in a gym. My naked chest somehow was all about sex! My naked body in the gym was somehow talking about sex! Some of my straight friends seemed okay if I never brought it up, so why talk about it? With my queer friends, I felt embarrassed that I had not had as much as I (should?) have had. I felt sex was another world.

I wish we all felt more comfortable talking about sex, about ourselves and sex. I’m 51 now, and it’s taken me this long to feel comfortable in my body, and talking about myself and sex. As a queer man, I saw that straight men had their sex talked about everywhere. If they weren’t repressed by religion, they could see a very narrow idea of their sexuality presented on TV, in movies, books, magazines. But even they were suffering from not talking about real sexuality. What a body really felt, really looked like, how it acted. Not what we’re told to look like — the idealized form that is impossible to become, or the idealized way of having sex.

I was lucky to have had some great moments with other men where I was allowed to be goofy and to laugh and to be a human being having fun and having sex. But it was also important to have an “out of body” experience –to see myself as a sexual person — so I could understand my body having sex.

For the first time, I really felt this joy for the person in the video. I felt empathy and love. And I wanted him to have a great time, and to find love and to find positive sexual experiences in his life. It allowed me to love myself in a whole different way.

I also got to be a director and filmmaker and work those filters!

I wasn’t going to do 75 of them, but I needed to see it once.

Evangelical religious dogma made me feel disgusted with my body for not being like other men. It made me feel ashamed to give in to passions. To have sexual feelings. To act on them.

I slowly tried to erase my body.

Over time, it worked. I had forgotten what I looked like.

But in that Studio of a Year, I got to know my body again as a work of Art. I got to meet the Jerome who felt sexy and unashamed of that. I got to send those unashamed, sex-positive images to friends and lovers to share that part of myself. I got the same back from them. In this way, sharing our bodies through pictures, we created encouraging support for our bodies with each other. By sharing those pictures, I affirmed their bodies, and they affirmed my body. It wasn’t just something that happened in the bed, or in the dark. It was a way of telling each other that we were good men. That we had great, positive, sexual feelings.

And for me, seeing myself was about getting love from the Divine too. Because I knew that while the studio was private to me, I think God was pretty happy I had discovered and loved my body too. Because they gave me that body, and they loved that body too.

After the studio was destroyed and remade into a gallery, I went to an art school. I felt inspired by my studio experience to paint positive pictures of fat queer heroes having adventures. I picked out Yukon Cornelius as my character to develop. He was in about ten minutes of a Rankin/Bass stop motion Christmas special, “Rudolph the Red Nosed Reindeer,” written by Romeo Muller. I wanted to give Yukon Cornelius a full queer life.

Now, I had planned to take photos of men that looked more like what I wanted Yukon to look like — strong, hairy, large, heroic — and I had friends lined up to be models. But schedules never worked out and time forced me to use what I had at hand to get my paintings done. So, with time dwindling, I had to substitute my own body in heroic poses.

It would just have to do right now till I could get those better bodies. Understand that I was at a point where I accepted my body, but I was not at a point where I thought my body could be, you know, heroic.

I took the pictures I had to — just to have a body to work with for the art.

And then, I looked at those pictures — and I was surprised.

Who was that?

That was me. I hadn’t changed or worked out or sculpted my body for this photoshoot. I was Just As I Am. In that moment, I realized I could be the queer hero too. It wasn’t a matter of just loving my body, myself. I saw that I — I could be the kind of hero I was looking for.

So, hey! I decided to pose for all my paintings of Yukon Cornelius. After all, I was used to taking pics of myself now!

My Front Street studio only existed for one year, and yes, I really did paint in that art studio. But it was my time in the studio that also taught me to see myself differently. Studio comes from the Latin studere — which gives us student, study. I was there to study myself through a new lens, through art. To be a student of my body from outside and inside my body. To be proud of my body, to be unafraid of my body. Studere also means “to direct one’s zeal” — zeal, enthusiasm! drive! I got to finally have zeal about my body. Be happy and enthusiastic about my body. To not be ashamed. To see my sexuality as human. To see myself as a sexual person– and not feel abnormal or sinful. In that studio, through that year long study, as a student, I was able to take back so much that had been taken from me. And, later, in my year of art school, still a student of my body and my art, I worked more of that out.

I am still working that out, every day.

It’s a process.

- Though this essay talks about the value of having an art studio outside your home, it is NOT necessary to be an artist. Studios can be expensive. I now have a great spot in my apartment that serves my needs. But this essay is about a studio and how it was an important catalyst for change.

_________________________________________________________________

If you’ve always wanted some time and encouragement to look at body image through art-making and writing, I have created a class for that.

Join me and other creators, art-makers, writers, online in October for 31 days of making art and writing to explore, think about, and transform your own ideas of body image and body acceptance. Email prompts with classical art, readings, and invitations to create art every day for a month, a discord channel and two zoom sessions to create together! I would love to see everyone have a studio experience like I had at Front Street that year–a chance to truly see myself for the first time. Come join us! Pay for the whole month, or pay $30 weekly! It’s all good!

— — — — — — — — — — — — — — — — — — — — — — — — — — — — — — — — — –

Jerome Stueart (2007 Clarion Workshop) is an American and Canadian queer illustrator, writer, and professional tarot reader. His writing has appeared in F&SF, Tor.com, On Spec, Lightspeed, Strange Horizons, Geist, and elsewhere. He was a finalist for a 2020 World Fantasy Award in Short Fiction for “Postlude to the Afternoon of a Faun” (F&SF). His PhD in English (Texas Tech U) with specialties in Creative Writing, Science Fiction & Fantasy, and Spiritual Memoir put him forever in debt, but has allowed him to live and work as a teacher part-time for more than 25 years, running writing workshops in academia and through city programming, in schools, in churches and online. He also has a background in theatre, history, tourism, and marketing. He was the former Marketing Director of the Yukon Arts Centre in Whitehorse, Yukon. An emerging artist and illustrator in watercolor and acrylic, he lives now in Dayton, Ohio.