You’ve seen the 1964 Rankin/Bass stop motion Christmas special, Rudolph the Red-Nosed Reindeer, written by Romeo Muller. It’s been aired on TV every year since it was first shown. You may have wondered, though, why Santa seems to be so MEAN-spirited in this movie (probably the only anti-Santa movie we show at Christmas time). There is a better Santa in this movie, though, hiding in plain sight.

CEO Santa Rules the North with a Manufacturer’s Mindset

Santa is the boss of toy-making and toy distribution, of all the elves and reindeer. When Rudolph is born, Santa blames Donner for having a “weird” son, and makes fun of Rudolph’s nose — — and of course, all of his “employees” do too. They’re just following Santa’s lead. His meanness and prejudice gets passed down to the reindeer. How can Santa himself be so narrow-minded!? This doesn’t feel like the Santa we know.

In a tale about manufacturing and production, this glowing reindeer and fabulous, dentist-oriented elf are merely flawed products. They are a version of an elf and reindeer who don’t do what those products should do. They are misfits like the toys they will meet later. The other elves, the other reindeer, do not want to accept them, as they have been taught to reject flawed toys.

Who do you think created the misfit toys? Those toys are typical manufacturing mistakes, tossed away. Losses. Victims of Quality Control. There is no love for a flawed product in a warehouse toy factory at the north pole. The elves must be VERY AWARE of their “mistakes”, even if they aren’t aware of the Island the misfit toys all eventually run to for safety.

I believe Santa is written this way on purpose — revealing the commercialized CEO Santa that’s kinda already there. Muller just reveals more of him because he has a doppleganger to compare Santa to. If Santa is the villain, and Rudolph is the hero of the story who has to grow and learn, then he needed a role-model for Rudolph to learn from, to really accept himself and others, since Santa won’t be modeling that.

This is the role given to the OTHER sleigh-driving big bearded man in the movie, Yukon Cornelius. I think this is done on purpose.

Yukon’s a character made up by writer, Romeo Muller, to expand the story beyond the original Robert May song. Muller doesn’t let this just be a song of Rudolph waiting till he’s useful to be discovered. That’s not fair to Rudolph. He creates someone better, a guide, a guru, a model to show Rudolph how to treat others, and himself, with radical acceptance and love.

Radical acceptance and love

Members of a group, a society, a culture, may“naturally” accept people who reflect back to them the kind of group they want to be seen as. So they might accept those who are like “us”, those who stay within expectations of social and moral cultural systems. Those who stay within the lines our group has drawn.

Hermey, though, is an elf who wants to become a dentist instead of a toymaker; Rudolph can’t really hide his bright, blinking nose and that makes him targeted by bullies. They are considered “unacceptable” by the groups they find themselves in — — not what they expect in an elf or reindeer. They don’t fit in, or won’t fit in. They won’t cooperate with what is expected. Rudolph tries to over his nose with mud. That’s not a permanent or acceptable fix for anyone.

When Rudolph and Hermey meet each other, they become besties! They have a lot of common experiences, in a way, commiserating over their differences. They reject societal norms! They are Rebels! They accept each other right away because they also want to be accepted! They go off into the world to do their own things.

They are all Abominable

Rudolph and Hermey aren’t safe in the world when they don’t play by the world’s rules. The Abominable Snowmonster is there to make them fear following their dreams. Noisy! Gnashing Teeth! Roaring! Chasing! GIANT! In a sense, as personified fear, he shows they will be unacceptable everywhere they go. He will relentlessly chase them down.

Who saves them from the Snowmonster? It isn’t Santa. Santa doesn’t even seem to know it exists, though I would say he is controlled by the fear himself.

Who HAS experienced that fear before — that fear of not being acceptable — and conquered it?

Yukon Cornelius.

Oh, he knows “Bumble”! He even reduces the scary words “abominable” and “monster” to rename him with a word for awkwardness. When we “bumble” through something, we bounce from one thing to another, without direction, we screw up, mess up, blunder, stumble. Bumble is a misfit too — and his name announces that he can’t “fit” either. Cornelius calls Bumble what he is — a socially awkward creature who is badly trying to fit in. He looks scary, and Yukon acknowledges that, but Yukon knows things about Bumble. He knows that Bumbles don’t like water and he knows they can bounce. He knows the strengths and weaknesses of Bumble. He sees through the scary part and sees the real Bumble, trying to survive alone. He will eventually save Bumble by giving him what he wants most: to be accepted with all his quirks.

Yukon Cornelius sees Hermey and Rudolph too. He sees them as who they are and who they want to be and immediately accepts them. He practices “radical acceptance” of everyone. Radical acceptance is acceptance BEYOND what you are comfortable with, what you’ve known, what is advantageous to you, or what might benefit you. You accept people for where and who they are. And you loudly support those you radically accept. Yukon is very loud. He is not afraid of anyone seeing who he’s with and who he supports.

The First Misfit

Long before they go to the island of Misfit Toys, we see that Yukon is already a MISFIT himself. He is a prospector obsessed with finding, not “silver and gold” as the snowman sings, as we are all led to believe, but a peppermint mine.

He doesn’t WANT what the rest of the prospectors — — or people want. He isn’t after money. He wants peppermint. Well that isn’t valuable, you might say. Why would a prospector be searching for peppermint? Prospecting is a hard life — — and would you go through the dangers of living in the wild, being outside of cities and companions, facing harsh weather, difficult, mountainous regions and digging through the earth — — just to find peppermint? The desire that makes Yukon different from ALL other prospectors is what makes Yukon a misfit. It seems to be a flaw. But I think it’s tied to his goals.

Santa has previously been characterized as judgmental: he knows if you’ve been bad or good. He has a list of naughty and nice people. He is a moral judge! If you are GOOD, you get blessings. If you are bad, you get JUNK. He is associated with worth and value, even commercial value, but also moral value.

Yukon, on the other hand, knows your strengths, allows those strengths to surface and guides you to use those strengths, even the ones others might dismiss. He is associated with seeking bliss, helping others, and he sees their innate value without judgment.

Yukon is set up to be a direct comparison to Santa.

Look at Yukon’s dog mushing team. This is radical acceptance in action! Whereas Santa’s sleigh has to be guided by “perfect” reindeer, Yukon’s sleigh is led by a mismatched group of sled dogs, that no one would believe would be good sled dogs: a St. Bernard, a dachshund, a sheltie, a beagle and a black poodle. We could think up a lot of reasons why this team of dogs wouldn’t work — -and yet, they work! Yukon believes in them, and they believe in themselves. They are all misfits but they love running and they run well together. They don’t know the proper commands (It takes them a while to understand “Mush” and “whoa” — “Stop” is what they have to hear to stop! Good luck teaching them Gee and Haw!) But in allowing them to be themselves, he demonstrates radical acceptance and love. He accepts the dogs for what they WANT to be, for who they know they ARE. And he lets them be that. And they show that they ARE good at what they love to do.

Yukon as the Better Santa

This is why I think Yukon contrasts so powerfully with Santa. They are similarly presented men — large, bearded, loud men with sleighs pulled by animals — but who act completely differently towards others. There are rules with Santa. There are not with Yukon.

Santa has to be convinced later into being accepting and giving . His acceptance of Rudolph comes when the reindeer can prove he can be of use NOT as a reindeer but as a beacon. Bumble, similarly, must be marketed as tall enough to put the Star on the Christmas tree. Thankfully, the presents from the island of Misfit Toys don’t have to prove themselves in order to be gifted at the end of the story to kids who will love them — but Santa must still be convinced to deliver them too. In fact, in 1964, with the original broadcast, Santa makes a promise to deliver them, but is never shown doing that, to which viewers complained that they wanted to see Santa keep his promise! In 1965, a new sequence was added to show Santa delivering the Misfit Toys to their new homes.

Even if you don’t understand the parallel set up of these two men as a kid, you GET the idea that Yukon accepts people and that Santa doesn’t. Yukon is the role model of this show, not Santa.

Yukon rescues, salvages, rehabilitates, transports, and teaches. He teaches Rudolph to value himself and to value others regardless of what kinds of expectations he may have, regardless of what they can do FOR him. Rudolph teaches Santa the same thing. I believe Yukon’s save of Bumble seals the lesson that no one is above acceptance.

When WE meet Yukon Cornelius

Growing up, seeing this show for the first time, and subsequent times, I think I saw myself as Rudolph, as many kids did — — someone who was not perfect, not wanted by other kids, not what adults thought I should be as a boy, but who had an important role to play in this “plot,” I hoped. I did not have a lot of positive male role models in my life who accepted me for who I was. I always felt like most boys and men were disappointed in me for one reason or another — I did not want to play hard, play sports; did not want to be mechanical; did not love the idea of the military as a proving ground for my manhood or patriotism. I did not know I was gay, and didn’t know I had ADHD. I was artsy and geeky. I was a misfit.

My parents did a great job to meet me where I was. Dad introduced me to Star Trek, comic books, science fiction. My mother read the Chronicles of Narnia to us in the hallway. These are enormous things! They also found and gave me for Christmas some very heady and scientific books on butterflies when I was interested in butterflies. I always got great gifts for Christmas — weird ones, but ones I cherished. My parents brought me things that transformed me for the rest of my life in good ways. They also were my first introduction to spirituality, and even though we eventually disagreed about some small things (that are kinda more important now) my faith began here. They gave me enough to grow my own faith and keep it strong, even as a gay man.

But my parents, like many people in the 70s and 80s, were still subject to the “rules” of society for gender. It was very hard for anyone not to be soaked in those rules. Guidelines for girls and boys and how they were supposed to act, what and who they should love, what they should do. We still have them. They are the basis for much pain and rejection even today.

Anti-Trans laws are directly influenced by previous theories about gender; anti-lgbtq legislation is also built on the backs of outdated gender theory. Gender is a cultural construct, and while many people are more aware of this, there are still many people who are afraid of people who don’t obey those gender rules — whether that is through gender expression or sexual orientation, or any other expression of gender and sexuality.

We should know better now.

But back in the 70s, these expectations were so much a part of our culture that I can’t honestly blame my parents for believing them. All the doctors, the newscasters, the psychologists, the media, not to mention all those in office. When your access to the truth is limited, you don’t get the truth, usually.

My parents did what they could to guide. In many ways, they protected me from much of the consequences others might have wanted to give me, and in their own way, they were practicing radical acceptance — as radically as they could within our family.

We end up on the Island of Misfit Toys

These misfit toys in the movie were rejected only because they didn’t DO what was expected of them. They were still of value and still interesting (as we come to see in the movie). Moonracer, the winged lion, comes across as God protecting the misfits from others — -but unable to, himself, fix their situation. It takes Yukon with Rudolph and Hermey to help bridge the distance between these undervalued people and those who could help them find their home.

I think we unconsciously gravitate to those who accept us. Perhaps, while the kids were enjoying the animation, the adults were learning a lesson about which sled-musher to follow, about how to accept others.

Me, I was looking for a Yukon Cornelius to see my value and worth, as many of us do.

I eventually found a way to bring Yukon to me.

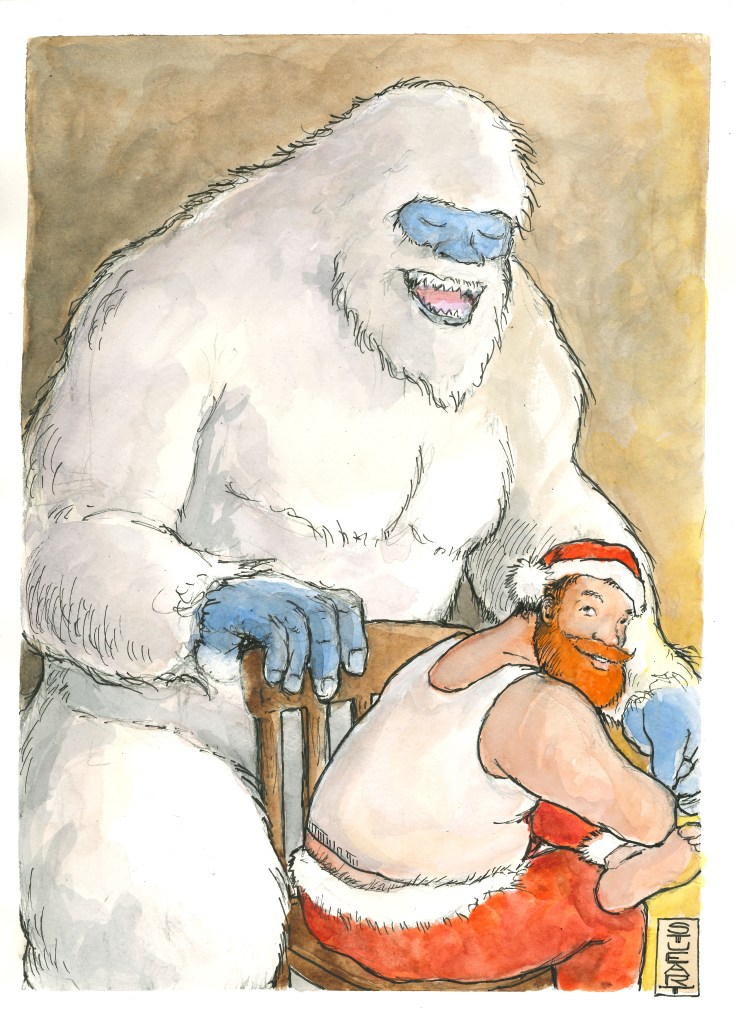

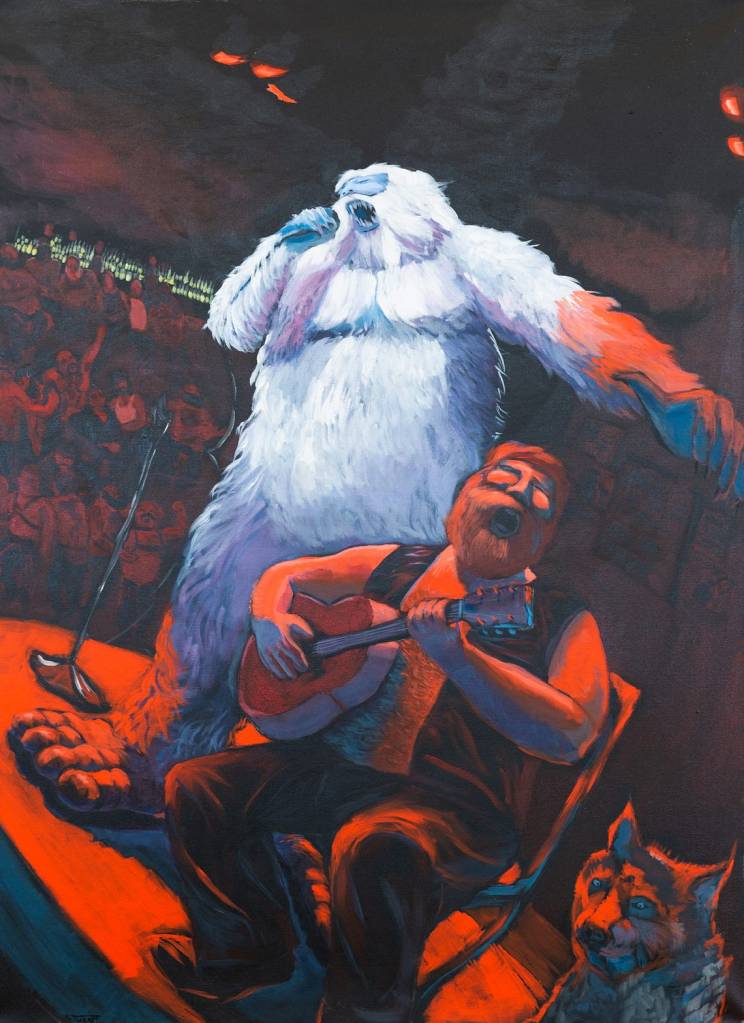

In 2019, I created a set of 10 paintings of Yukon Cornelius in the style of NC Wyeth — a style of boy’s adventure books popular in the early 20th Century, to explore what a gay hero might look like to me — the kind of gay hero I wish I could have had growing up. In 2022, I completed a show of about 50 paintings, acrylic and watercolor, with stories to go with them, titled, “The Further (Queer) Adventures of Yukon Cornelius,” where he went out to help other cryptids sometimes with his partner, Bumble. It gave me a gay hero that I would have loved to have read more about. We only got 10 min of Yukon Cornelius in “Rudolph” but it made me want to see what might happen if we had more time with him. Who else could he radically accept?

The Queer Connections

Yukon is the Santa we want to believe Santa is. Inclusive, accepting, encouraging, helpful, transformational. I think Romeo must have put this in here intentionally. As a writer, I can’t see this parallel as anything but intentional. Especially regarding the themes, and knowing Romeo made up the whole plot himself outside of Rudolph’s original rejection. I know you’ve probably come across a couple of articles that look at the gay themes in this show — -but wow, they certainly hit LGBTQ people strongly, whether or not they were intended to.

ALL people can identify with being rejected at one point in their lives for not being what other people thought they should be, which is why this movie has lasted for 59 years, being shown every year (I think it’s considered the longest running annual show on TV). It tapped into something universal. Rejection is HUGE for kids, and the fear of rejection is paralyzing. We are all, in some ways, a misfit.

But I do believe there is a specificity of rejection present here. Something queer kids know too well. When Donner is blamed for his son’s behavior, that Rudolph is not what his father wants him to be, and that this gets Rudolph banned from a place in society, that really hits so hard for queer people I think. To me there is a strong queer undertone for the KIND of rejection Rudolph goes through and the KIND of rejection that Hermey faces. They face shame for their different desires, their different aspirations, and their families are shamed too.

In this film, I believe Yukon Cornelius is a model for a better version of Santa. I think Romeo Muller wrote that on purpose, writing parallels to Santa into the DNA of Yukon Cornelius, in order to highlight their similarities and differences. I think he wanted us to rethink the way we “gift” others with our friendship and our acceptance. Are we here to judge them, to find out if they are naughty or nice, and then decide whether they are acceptable, or misfits?

No, I think we’re here to be more Yukon Cornelius. We are here to befriend, belove, rescue, support, transport, help, and accept people where they are, and for who they are. We all need a little more openness in our sleigh, to carry people, and not just our things, our job. We need to be able to detour away from our agendas at times and help out others with their agendas.

Perhaps today, Santa could learn some tips and could shed the “nice” and “naughty” criteria, allowing universal access to benefits and beneficence by practicing a little radical acceptance of his own.

Jerome Stueart (2007 Clarion Workshop) is an American and Canadian queer illustrator, writer, and professional tarot reader. His writing has appeared in F&SF, Tor.com, On Spec, Lightspeed, Strange Horizons, Geist, and elsewhere. He was a finalist for a 2020 World Fantasy Award in Short Fiction for “Postlude to the Afternoon of a Faun” (F&SF). His PhD in English (Texas Tech U) with specialties in Creative Writing put him forever in debt, but has allowed him to live and work as a teacher part-time for more than 25 years, running writing workshops in academia and through city programming, in schools, in churches and online. He also has a background in theatre, history, tourism, and marketing. He was the former Marketing Director of the Yukon Arts Centre in Whitehorse, Yukon. An emerging artist and illustrator in watercolor and acrylic, he lives now in Dayton, Ohio.