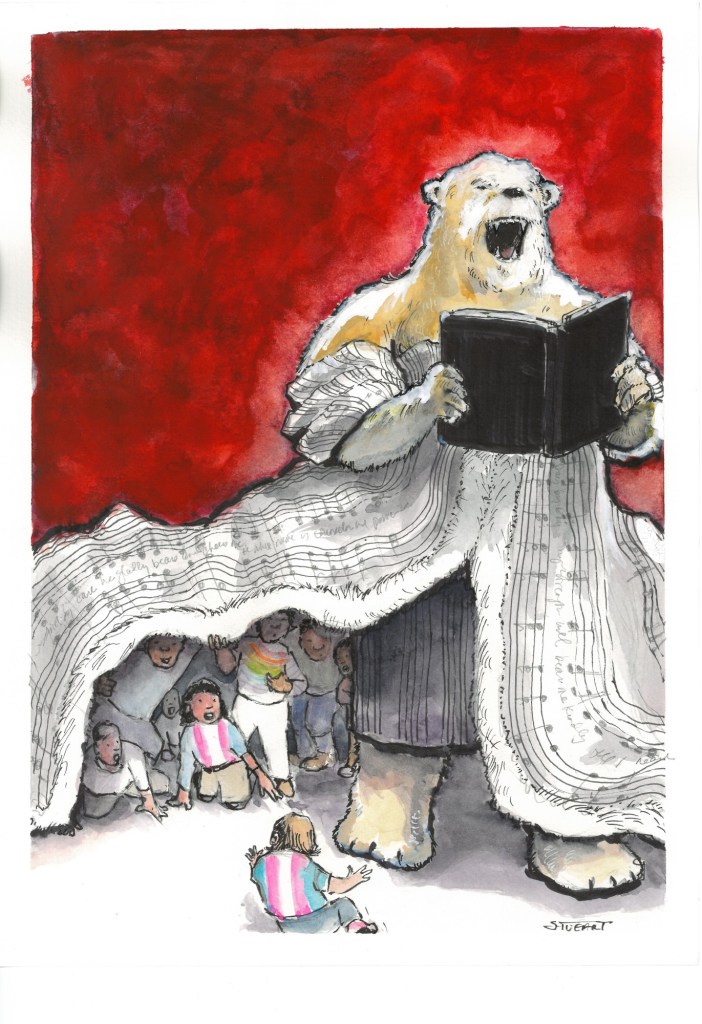

When I came out in 2009 to my church, it did not go as I’d hoped it would. But it was music that strengthened me. According to Hymnary, a database of all hymns and hymnals online, there are 6,165 bears in hymns that have been used in Christian churches. They might be “bearing the cross” or “bearing one another’s burdens” or ask us to help them “bear the light” or ask God to “bear us safely over.” Many hymns sung every week have a bear in them. Because I identified with the “bear” community of gay men, I felt like this was a little love note sent by God every Sunday to strengthen me, and so I would sing the hymns as I always would, but I’d be extra loud and strong on the word “bear.”

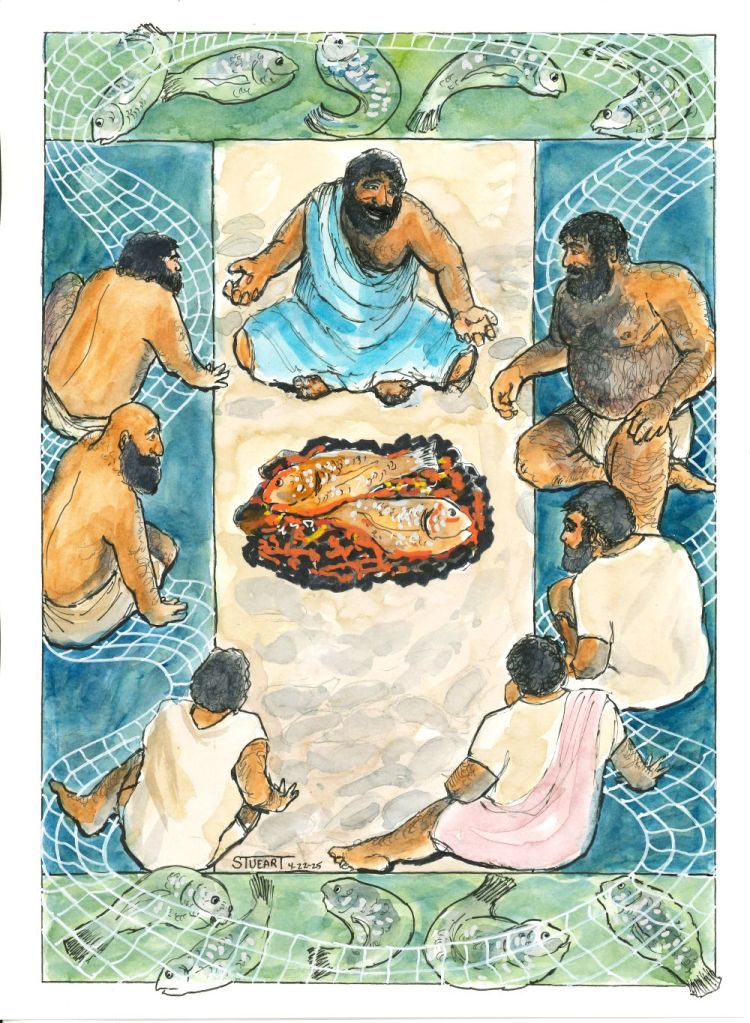

I’ve mentioned before that I had some leftover grief from that time fifteen years ago, some that bubbled up while I was watching Star Trek with Joey one night. I cried so hard and didn’t know why. I thought I’d worked through all of that years ago. So I went on a journey to find healing. Part of that journey involved creating 9 paintings that I want to share with you. They are images crafted by grief and pain and hope. I did them intuitively, just listening to what my heart was upset about, what it wanted to say, what it wanted to see. I discovered all these protective, strong bears were still there in my head and heart. Many of these paintings surprised me, but they also make my heart glad to see them. And I’m glad to start sharing them with you. I hope they make you glad too.

Originals and prints are available in the comments.

“Day by Day, He Gladly Bears and Cheers Me,” (11 x 15) Jerome Stueart, watercolor, mixed media on paper.